140 years ago, 74-year-old Joseph H. Purington was robbed and murdered in Bath, Maine

IN THE LAST EPISODE OF SEASON ONE, WE TRY TO DO THE IMPOSSIBLE AND USE MODERN TECHNOLOGY TO SOLVE A MURDER

In our tenth and final episode of Season One, we have some fun with history by trying to solve a 140-year-old murder mystery. The episode is available on all major podcasting platforms, including Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, and YouTube. You can find Company D on your favorite podcasting app here:

Or listen to the episode here:

Transcript for Ep10

The frantic knocking brought Joseph Emery Purington to his front door. The former corporal with Company D of the Third Maine Infantry Regiment found one of his father’s co-workers at Deering & Donnell, a shipyard on Washington Street in Bath, Maine, on his stoop. Emery recognized him as Ebenezer Allen.

“It’s your father,” Allen said, his voice thick with emotion. “He’s in trouble.”

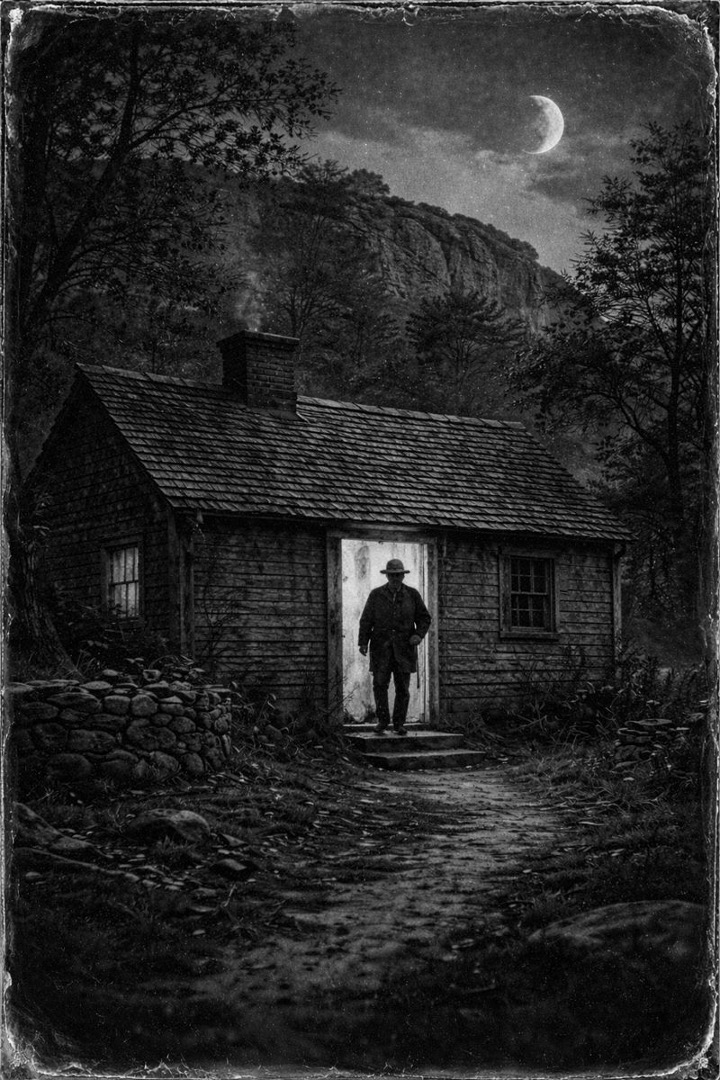

Pausing only long enough to grab his hat, Joseph followed Allen, and they hightailed to his father’s neglected two-room dwelling on High Street. His father’s isolated house resembled a shack, set back from the road in front of a pine forest and a rocky ledge.

The front door was ajar. Bursting through the doorway, Emery found his 74-year-old father lying face down on the plank floor. His father lay on his right side with his arm pinned behind his back. He was unconscious and covered in blood and vomit.

As they helped his father, Emery noticed extensive bruises on his father’s face. His father’s valise, usually kept locked and hidden, lay open on the floor, empty. His wallet was also missing. There was no money in the house; it was all gone.

Two days later, the elderly Joseph Higgins Purington died without regaining consciousness. The newspaper headlines in Bath and across Maine cried, “Murder!”

The public wanted answers. Unfortunately, they never got any.

Until today.

Because today on Company D, we’re going to try to solve a murder. A murder that took place 143 years ago.

Hello and welcome to Company D, the history podcast that explores the personal stories of the average soldier who fought in the American Civil War. Our mission at Company D is to share the compelling true-life stories of individual soldiers from one regiment, the Third Maine Infantry Regiment, and one company within the Third, Company D.

One regiment. One company. Countless stories.

The soldiers of Company D of the Third Maine came from Midcoast Maine, primarily around the shipbuilding city of Bath. These men were farmers, fishermen, and carpenters until they donned the blue uniform of the United States Army and fought to bring an end to slavery and reunite the United States of America.

We’re not interested in the big history of the American Civil War—the politics, military tactics, and the stories of the politicians and generals. We’ll leave that to more qualified experts.

We’re here for the real people—the soldiers and their families who lived through one of the most seismic historic events in U.S. history, and how the war and its aftermath forever shaped their lives.

This is microhistory at its finest. At least, we hope so.

Why did we choose to focus on Company D of the Third Maine? Because for us, this is personal. My great-great-grandfather, Charles F. Snell, volunteered with them. Charles left a diary of his experiences in the war, which has become the inspiration for this podcast.

I’m your host, George F. Snell III. Because two is company and three is a podcast.

Today, on Company D, we’re venturing into crime drama. We’re bringing you a dark and mysterious true-life story filled with morally ambiguous characters and a gritty urban setting. This is a true story, but one that could have been penned by two of our favorite crime writers, Peter Swanson and S.A. Crosby.

Let’s call today’s episode Company D Noir.

A cantankerous old man, rumored to be a wealthy miser and who has strained relations with his dysfunctional family, is found battered and bloody on the floor of his isolated house. The old man’s wallet is missing, his locked valise is opened and empty, and the premises have been cleared of all the cash he allegedly hoarded inside.

What happened to Corporal Joseph Emery Purrington’s elderly father on the rain-soaked night of September 27, 1882, has remained a mystery for more than 143 years.

Despite pressure from newspapers, politicians, and the family, no one ever solved the case, and it faded into history.

But that ends today.

Today on Company D, we play gumshoe. We put on our trench coat and deerstalker cap. We dust off our magnifying glass and our long-stemmed cherrywood pipe because we’re going to play the part of Sherlock Holmes and try to solve a centuries-old mystery.

Who killed Old Man Purington? And why?

In this episode, our 10th and last of our first season, we’re going to try to uncover what truly happened to Joseph Higgins Purington in 1882.

And identify the most likely suspect.

The game, my friends, is afoot!

CHAPTER ONE: A BUNGLED INVESTIGATION

Before we begin, it’s important to understand why the case was never solved. Let’s take a closer look at the crime scene and the law enforcement situation in Bath, Maine, in 1882, the year 74-year-old Joseph Higgins Purrington was found beaten on the floor of his house. This might help explain why the case has remained unsolved for 143 years.

Bath’s population in the 1880s was nearly 8,000. The city was recovering from a decline in residents, mainly due to the significant death toll of the Civil War. From 1860 to 1870, the city’s population dropped by almost 9 percent, marking its first population decrease in more than 70 years.

As a port city, Bath had its share of boarding houses, taverns, gambling dens, and brothels. Brawls and public intoxication, despite a prohibition against alcohol in Maine, were not uncommon. The late 19thcentury was significantly more violent than the United States is today. The murder rate for the century was 20 per 100,000 people. Murders dropped to 10 per 100,000 in the 20th century; today, the rate is about 6 per 100,000.

You were three times more likely to be murdered in the 19th century than you are today.

However, crime fighting was still in its early stages. In the 1880s, police departments were not professional organizations. Like most cities of its size, Bath had a politically appointed City Marshal who reported to the mayor and the City Aldermen. He oversaw a team of constables and night watchmen who primarily broke up fights, arrested drunks, conducted liquor raids, and generally enforced local ordinances such as leash laws. They were amateurs with no professional standards or training. Forensic investigations were beginning to develop, with only a few large city departments adopting modern crime-solving techniques such as fingerprinting, photography, and interviewing.

In 1882, Bath’s City Marshal was William H. Gilman, a 58-year-old teamster. He oversaw twenty constables and night watchmen. A war veteran, Gilman served nine months as a wagoner with the Twenty-First Maine Infantry Regiment. He was City Marshal for just one year—the year Old Man Purrington died.

Gilman was appointed marshal in the winter of 1882 and spent most of the spring in an ugly feud with Nightwatch Captain James Bailey. Bailey, a 60-year-old former tugboat captain, had lost his arm in a gun accident in 1849. Gilman and Bailey despised each other.

Their feud went public in May during an Aldermen hearing. Gilman accused Bailey of insubordination, dishonesty, and slander. In response, Bailey claimed that Gilman possessed low morals and sought the company of “lewd women.” “Lewd woman” was a euphemism for a prostitute in the 1880s.

Bailey alleged that at least two women had approached him for assistance in deterring Marshal Gilman’s unwanted advances. Bailey even reported Gilman’s alleged sexual misconduct to the mayor.

On a side note, my great-great-granduncle, George Snell, who operated a furniture shop on Front Street in Bath, was a witness at the hearing. George was among several people who saw Gilman and Bailey shouting at each other on the street.

In a narrow vote, the Aldermen sided with Marshal Gilman, dismissing Bailey’s accusations as unfounded. Bailey ended up being suspended from his role as Nightwatch Captain.

Yet, Bailey was reinstated several months later and succeeded Gilman as City Marshal the following year. But after the scandal, Gilman kept himself busy arresting drunks, conducting liquor raids, and chasing after boys sledding on city streets. When Old Man Purington was found unconscious and bloody in his house in September, Gilman was clearly over his head in conducting a murder investigation. Not to mention distracted.

Maine newspapers widely criticized him for his investigation into the Purington case. No one was ever arrested, and the investigation couldn’t even determine whether, in fact, Old Man Purington was even the victim of a crime.

These disappointing results were likely the main reason Gilman was Marshal for only a year before being replaced by the man he had fired.

CHAPTER TWO: WAS JOSEPH HIGGINS PURINGTON EVEN MURDERED?

The Bath Coroner’s jury could not reach a decisive conclusion about whether Old Man Purington was a crime victim, leaving his family, the city’s politicians, the general public, and the region’s newspapers baffled. And then angry.

The jury’s verdict read:

“That the said Joseph H. Purington came to his death Friday, September 29Th, A.D. 1882, from concussion of the brain, produced by wounds received between Monday evening, September 25th, and Wednesday afternoon, September 27th, but by what means to the jurors, unknown.”

The coroner’s report left open the possibility that Old Man Purington could have suffered a seizure and struck his head on his stove while collapsing to the floor.

Most people roundly rejected the jury’s conclusion, due to Purington’s missing wallet, his open valise, his missing cash, and the sheer extent of the blood and bruises on his head, shoulders, and face.

The public outcry was swift. Bath’s Mayor James Ledyard and the Board of Aldermen quickly authorized a reward of $500 for the discovery of evidence that would lead to a conviction of “the person or persons who committed the assault on Joseph Purington or who were accessory to his death.”

Given the preponderance of evidence, it seemed evident to us at Company D that Old Man Purington was the victim of a homicide.

We wanted to be sure, so we decided to collect the available evidence and run it through the Generative A.I. platform, ChatGPT. We uploaded more than a dozen articles summarizing the case, the coroner’s report, and the eyewitness testimony, and asked ChatGPT if Joseph Higgins Purington was murdered.

Here is ChatGPT’s conclusion:

“Based on the available evidence, there is a 97% probability that Joseph H. Purington was murdered. While the coroner’s inquest did not entirely rule out the possibility of a fall as the cause of death, that explanation is undermined by the nature of Mr. Purington’s injuries — multiple blunt-force wounds inconsistent with a typical accidental fall — and by the suspicious circumstances surrounding the discovery of his body, including the open and emptied valise where he was known to keep money. The combination of violent trauma, missing cash, and lack of other plausible accidental scenarios strongly supports the conclusion that his death was the result of intentional foul play.”

Generative A.I. is not conclusive evidence, but based on everything we can find in the case, we think it’s safe to conclude that yes, Joseph Higgins Purington was murdered.

CHAPTER THREE: THE VICTIM

In 1882, Joseph Higgins Purington was 74 years old. Despite his advanced age, he worked as a ship’s carpenter at Donnell & Deering’s shipyard on Washington Street on the city’s south end. He also owned an interest in three trading ships based in Bath. He was widely considered to be a wealthy miser, living below his means in a low-slung hut on High Street that he had built himself.

Old Man Purrington had been separated from his wife, Joanna (Spinney), for at least three years. Joanna said she frequently visited her estranged husband to cook his meals and clean up after him. Joanna lived with her son and daughter a short distance away on Middle Street. She blamed her separation from her husband on “incompatibility of temper.”

Old Man Purington and his son, Joseph Emery, also had a strained relationship. Emery said that although he rarely argued with his father, they had an unfriendly relationship. He called his father an eccentric and a difficult person to get along with.

Neighbors often noticed Old Man Purington coming in and out of his house. They said he kept to himself and had an unusual walking style, with his head bobbing forward in a peculiar manner as he walked. Most had heard the rumors that he had money hidden inside his house, but they generally viewed him as honest and hardworking.

Old Man Purington was born on October 8, 1808, into a large farming family on the outskirts of Bath. At the time of Joseph’s birth, Bath was swiftly transforming from a rural community along the Kennebec River into a shipbuilding boom town. By 1850, the city’s population had quadrupled, from 2,000 to nearly 8,000.

When he was 24, Old Man Purington married Joanna Spinney from Georgetown, Maine, on December 16, 1832. Nineteen-year-old Joanna was the sixth of eight children born to fisherman Nicholas Spinney and his wife, Susannah (Burgess).

Together, Old Man Purington and Joanna had five children: Joseph Emery, Susan, Sarah, Margaret, and Alvah.

During the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s, Old Man Purington spent a couple of years in California. At that time, he was in his late thirties and had left behind his wife and five children. Hundreds of thousands of men, many from Maine, traveled to California in hopes of striking it rich. Rumors suggested that when Old Man Purington finally returned to Bath in 1850, he came back with a small fortune.

Old Man Purington worked as a carpenter in the shipyards and also managed to invest in ownership stakes in several trading schooners.

The family experienced a traumatic period in June 1853 when the two youngest Purington children, Margaret and Alvah, died within two weeks of each other. The culprit was likely a contagious disease such as diphtheria or typhoid fever, but no cause of death was given for either child. Margaret was nine, and Alvah was five when they were buried at Maple Grove Cemetery.

Old Man Purington lived in Bath, raised his three remaining children, and worked in the shipyards.

When he separated from his wife around 1879, Old Man Purington lived alone in his small house on High Street and rarely saw his family.

CHAPTER FOUR: THE OLDEST SON

Old Man Purington’s eldest son was Joseph Emery Purington. He went by the name Emery. He was born on July 8, 1833. Emery graduated from high school in Bath and, like his father, spent most of his life working as a ship’s carpenter.

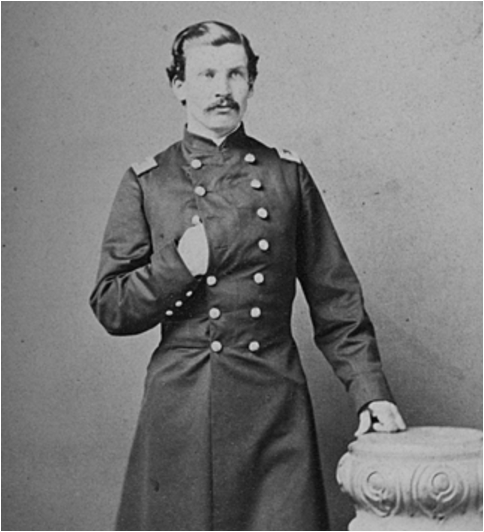

In 1861, Emery enlisted in Company D of the Third Maine as a private. When he volunteered, he was 27 years old, standing five feet seven inches tall, with hazel eyes, dark hair, and a dark complexion. His looks favored his mother’s side of the family.

Emery had an eventful three years with Company D and, like his father, seemed to possess a talent for being in the wrong place at the right time. Shortly after enlisting, Emery claimed he had not been paid his signing bonus of $26—a claim refuted by his enlistment officer, who insisted that he had paid Emery personally. It’s unclear how that dispute was resolved.

After the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August of 1862, the Third Maine was retreating with the rest of the Union forces when the Confederates cut them off at Chantilly. The Third Maine engaged in heavy fighting, with four killed, 38 wounded, and eight missing. Emery was initially reported killed in action.

At least two news articles were published in local newspapers reporting that Emery was dead. The news must have been devastating for his parents and two surviving sisters. However, he was only missing in action and soon turned up.

One month after that error, he was promoted to Corporal. Emery would disappear again eight months later, on May 3, 1863, during an ill-fated midnight attack at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Chancellorsville was another disastrous loss for U.S. forces in Virginia. At dusk, the Rebels obliterated the Eleventh Corps, and Union General Joseph Hooker, desperate for his troops not to be completely overrun, launched a series of counterattacks.

At 9 p.m., huddled around campfires in the mounting darkness of the dense Wilderness woods, the Third Maine received orders for a midnight offensive. The news unsettled many of the men, who were worried about fighting in the darkness amid the tangles of vegetation. Some of the men wrote farewell letters to their families, pinning them to their sack coats. They affixed their bayonets in the light of a full moon.

The goal was to take a breastwork near Plank Road. It was a terrible charge. The well-fortified Confederates, many from the Eighteenth North Carolina Regiment, waited for the Third Maine to leave the woods to an open pasture bathed in moonlight before opening fire.

Corporal Charles F. Snell of Company D remembered the fight this way: “About 11 o’clock at night our Brigade was put in front and ordered to charge into the woods and drive the Rebels back so as to make a connection with the rest of the Army.” Snell continued, “It was done, and a terrible charge it was, too. The Rebels did not fire till we got right on to them, and then they gave us a Volley which I shall never forget.”

The Third Maine suffered severe losses of four men killed, 17 wounded, and 42 missing. Even worse, as the Third Maine fell back toward their own lines, it was fired upon by the Union Army’s Twelfth Corps, who mistook them for an enemy charge.

Emery and Private George Bliss of Company D went missing in this chaos.

Once again, it’s unclear what exactly happened to Emery. He fell off the muster rolls of Company D after being listed as missing in action following Chancellorsville. Two months later, he was absent from Company D at the Battle of Gettysburg. Both Emery and Bliss returned to the company on November 1. Both of them were likely captured by Confederates, held as prisoners of war, and released as part of a prisoner exchange. There’s no documentation of that, so we don’t know what actually happened to them.

At the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864, Emery was captured once again. Late in the afternoon, the Third Maine was ordered forward as reinforcements to stabilize the Union front line, only to run straight into the Twelfth North Carolina Infantry Regiment.

Emery was captured at the same time as Corporal Charles Snell. On that day, Snell wrote in his diary: “About 3 o’clock p.m., the first day’s fight commenced. Our Regiment advanced in the woods. It got nearly surrounded. I was taken prisoner by the 12th North Carolina. Marched through the Rebel lines about 10 miles and camped down for the night.”

Emery and Snell were imprisoned together at Andersonville Prison in Georgia and the Florence Stockade in Florence, South Carolina, until December 5, 1864, seven of grueling months of captivity.

Emery was officially discharged from the Third Maine on February 23, 1865, and returned to Bath in poor health, struggling to find steady employment as a result.

He was forced to move back in with his parents and younger sister, Sarah. Emery continued to have health issues, and while he found work as a carpenter, he struggled financially. He filed a disability claim with the U.S. government in 1878 and made several dubious claims—that he had been shot three times, fought in more than 23 battles, and that he achieved the rank of Sergeant. There’s no evidence of any of those claims being true.

After years of disputes with the U.S. government, Emery finally secured a meager pension on March 14, 1882, six months before his father was killed. He attempted to receive back pay dating to 1878 but was denied.

In the months leading up to his father’s murder, Emery was involved in a financial dispute with his father regarding the future of his sister’s children. We’ll get to the details about his situation in a moment.

But there is little doubt that, given his own financial challenges, his close familiarity with his father’s house and possessions, and his complicated relationship with his father, Joseph Emery Purrington is a suspect in his father’s murder.

CHAPTER FIVE: THE OLDEST DAUGHTER

Susan Elizabeth Purrington was the oldest daughter of Old Man Purington and his wife, Joanna. She was born on September 9, 1835, in Bath.

Susan, who worked as a tailor, lived with her parents well into her twenties. At some point, she met an Irish-born pressman named Michael J. Kelley. Kelley was Roman Catholic and grew up in Boston—he was baptized there on April 23, 1837.

The reasons and manner of Kelley’s move from Boston to Bath remain unclear, but he arrived shortly after a period of intense prejudice against Catholics, especially Irish Catholics, in Bath. Throughout the 1850s, Bath saw several anti-Catholic incidents, including a riot on July 6, 1854, when a mob set fire to the Old South Church, a church that had recently been purchased by Irish Catholics.

The police made no arrests, and the Fire Department gave the arsonists three cheers of support. The tensions calmed once the Civil War started, but it wasn’t easy being Irish Catholic in Bath when Michael J. Kelley arrived. It’s unclear how receptive Susan’s family was to her being romantically linked to an Irish Catholic.

Kelley returned to Boston and enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a substitute on June 15, 1864. He had made a financial arrangement with someone who had been drafted into military service to take their place—for a price. Substitutes were usually paid around $300 to take the draftee’s slot.

Whoever paid for Kelley, however, got a bad deal. He deserted from the U.S.S. Ohio after serving for six months, a practice known as bounty jumping. The practice was illegal, and desertion was punishable by death. Yet despite the consequences, many substitutes, often known derogatorily as hirelings, often collected their bounties and bailed.

Kelley appears to have been one of these men.

After deserting, Kelley fled to Boston, where Susan met him. They married in a Catholic ceremony on July 23, 1865, after the war had ended and Kelley was less likely to face arrest or prosecution for desertion. They then returned to Bath and had two children: Margaret, born in 1866, and Alvah, born in 1868. Susan named her kids after her two deceased siblings.

Kelley likely faced scorn from Susan’s family, not only for being a foreigner and a Catholic, but for his criminal behavior during the war. After all, Susan’s brother, Joseph Emery, was honorably discharged as a corporal and spent a significant amount of time in Confederate prisons.

Regardless, the marriage didn’t last long. Kelley separated from Susan before 1870. Susan moved next door to her father, whose household included her mother, brother, Emery, and her sister, Sarah. Her father supported Susan as she raised her two children.

Kelley remained in Bath, where he continued to work as a pressman. At some point, he was in such dire financial need that he borrowed money from his father-in-law, Old Man Purington, and promptly fled the state, most likely to Boston, officially abandoning his wife and two children—and taking his unpaid debt to Old Man Purington with him.

In 1877, Old Man Purington sued his son-in-law, demanding that Kelley repay his debt of more than $1,000. Old Man Purington was so angry that he was also demanding additional damages of $1,500. Kelley was ordered to appear in court in Bath within 30 days; however, he never showed up, and the debt or damages were apparently never repaid.

Tension was rising between Kelley and Old Man Purington. Their situation was about to worsen.

CHAPTER SIX: A DEATH IN THE FAMILY

Shortly after suing Kelley, Old Man Purington moved into his hut away from the rest of his family, although he had Susan and her two children reside with him. The rest of his family, his wife, son, and other daughter, lived elsewhere. His wife, Joanna, stopped in several times a week to cook and clean for him.

In 1882, Kelley filed for a divorce from Susan. However, before the case could be heard in court, Susan died unexpectedly on September 2, 1882. She left behind her 16-year-old daughter, Margaret, and her 14-year-old son, Alvah.

It’s unclear whether Kelley wanted custody of his children, but it seems unlikely, given that he had been living in Boston without them for several years. Old Man Purington covered the cost of Susan’s funeral and burial, which amounted to about $40. The family decided that Emery and Sarah would raise their niece and nephew, with Old Man Purington financing their upbringing.

During the coroner’s inquest into his father’s death, Emery testified that Kelley was an unfit father and had not been in Bath for nearly eight years.

Emotions were running high in the Purington family. Susan was dead, leaving behind a messy and complicated domestic situation. Her husband, whom the family disliked immensely, was lurking around Bath, refusing to take responsibility for burying his wife or providing for his children.

Why had Kelley returned at all? He was being sued for thousands of dollars by Old Man Purington. He had initiated formal divorce proceedings against Susan before she died (in fact, the court would grant the divorce in December, despite Susan already being deceased). And the Purington family clearly disliked him.

But there he was—back in Bath. Did the bitter and bankrupt Michael J. Kelley visit Old Man Purington on the night of his death? Did Michael Kelley kill and rob his estranged father-in-law? We know one thing—right after Old Man Purington was killed, Michael Kelley went back to Boston.

No doubt about it. Michael Kelley is a suspect.

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE LEAD-UP

The last time Emery saw his father was on Saturday, September 23. Their paths crossed at the Lower Methodist Church after 5 p.m. at dusk, as a waxing gibbous moon rose over the church steeple.

“We were not exactly friendly,” Emery confessed during the coroner’s inquest. “But we never quarreled; our unfriendliness was the result of mere differences in opinion.” Emery continued, “He was an eccentric man, peculiar and hard to get acquainted with.”

On Monday, September 25, a neighbor was the last person to see Old Man Purington before he was attacked. The old man walked at dusk, in the rain, toward his house.

The weekend passed. Old Man Purington didn’t show up for work on Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday. That’s when his co-workers decided to check on him. Ebenezer Allen and David Clark found him in a bloody heap on the floor, still alive. They called for a doctor and ran to fetch Emery.

Old Man Purington was still wearing his rubbers, and there was no doubt in their minds that he had been lying on the floor since he had last been seen on that stormy Monday night.

Emery was convinced his father had been attacked and robbed. “They left him to die, in my opinion,” he said at the Coroner’s inquest. Emery said the robber would have needed to injure his father because he was a spunky old man and would have “fought as long as there was breath in him.”

Old Man Purington lingered, but never regained his senses. He died at noon on Friday, September 29.

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE VERDICT

It’s been 143 years since Joseph Higgins Purington was found face-down on the floor of his High Street shack—bloody, broken, and robbed. And in all that time, no one has ever been held accountable. No trial. No suspect. No confession. Just silence and speculation.

But history doesn’t forget. And neither do we.

We’ve already determined (with the help of modern technology) that Old Man Purington was murdered. He was attacked. Deliberately. Violently. And with purpose. The open valise. The missing wallet. The bruises. The blood. A fall doesn’t explain that.

Old Man Purington was beaten and left to die. The Bath police in 1882 didn’t have the tools, or perhaps the will, to solve this crime. But we do.

Let’s turn back to modern technology. We fed all the evidence: the case files, the newspaper articles, the Coroner’s report, the court and inquest information back into ChatGPT and asked it to determine who killed Old Man Purington.

Keep in mind, this is speculation for entertainment purposes only. We can’t know definitively who killed Old Man Purington, and neither can an AI program. That said, let’s see what our Robot Overloads came back with.

First, let’s look at who ChatGPT eliminated: Joseph Emery Purington, the son. Why?

We’ll let the robot explain:

“Joseph Emery Purington didn’t kill his father because he had nothing to gain, fully cooperated with the investigation, and was called to the scene by another witness, not discovered there himself. His actions showed urgency, not guilt, and unlike others, he wasn’t desperate or hiding anything.”

Now, let’s turn to who ChatGPT believes is the murderer.

“Michael J. Kelley is the most likely killer because he had the strongest motive, the greatest desperation, and perfect opportunity. Just weeks after his estranged wife’s death—paid for by Joseph H. Purington—Kelley returned to Bath for the first time in years, still owing his father‑in‑law thousands of dollars from an old lawsuit. He knew where Purington kept his cash, had no custody of his children, and faced both humiliation and financial ruin. The robbery of the valise and wallet, combined with Kelley’s sudden reappearance and rapid disappearance, make him the only figure who clearly fits motive, means, and opportunity.”

There you have it. Our own Minority Report verdict. Michael J. Kelley. Let us know what you think of the verdict or if you have one of your own.

We’ll end Episode 10 and the first season of Company D with this quote from Sherlock Holmes, “When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Thank you for listening to the final episode of our first season of Company D. We appreciate your support in bringing these stories to life. Don’t worry. We’re already researching and writing Season 2, but first, we’re going to run a Kickstarter campaign. We’ll let you know the details soon.

Season 2 is scheduled to start this spring with 14 brand-new, true-life stories.

One Regiment. One Company. Countless Stories.

Be sure to visit our website at companydpodcast.com to take a peek at the case files and notes on the case of the Mystery of the Mangled Miser.

We love receiving your questions, comments, and feedback. Please follow us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, TikTok, YouTube, and on Bluesky.

I’m your host, George F. Snell III. See you next time. And remember—don’t be criminal. Be civil.

Leave a Reply